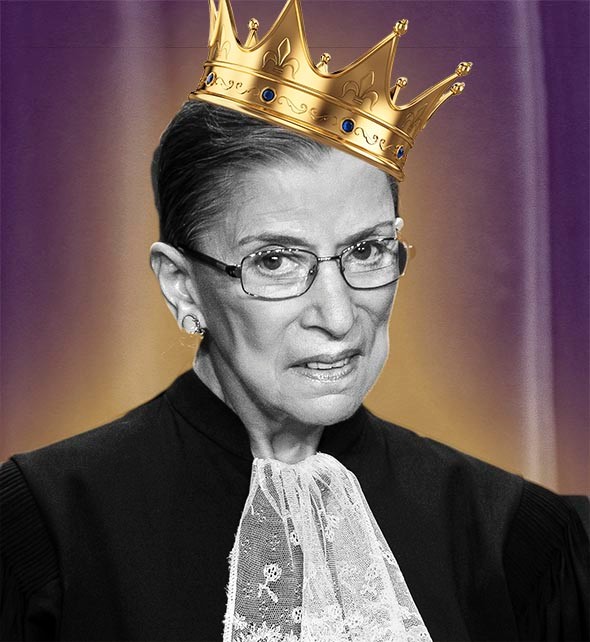

I recently saw the new documentary film, “RBG,” about the life of the nation’s second female Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The film is definitely one to see. It is a comprehensive view of her life and work. It made me laugh and cry and gave me hope for the future. I learned of Ginsburg’s personal life and her outsized contributions to women’s rights over her nearly seventy years in law. The film’s title is a riff off the moniker of the Rapper Notorious BIG. Since Ginsburg has been declared by many on the political Right as “notorious” and “evil,” this seems apt. It also showed the fan base she has among the nation’s young. She has rock star status, a complete surprise to me.

“RBG” also sparked rich memories about my own career. I arrived in the nation’s capital after college in 1973 as the second wave of feminism was hitting its stride. I was fortunate enough to land a good job in the international division of a labor union, an early career goal. My boss was a feminist committed to advocating for an enhanced role for women in the labor movement.

When I first began working, I was too focused on my own endeavors to take in that I was part of a growing force of women that included intellectual giants such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As time went on, however, I met more and more women on the front lines: labor advocates and workers, professors, diplomats and lawyers. Their common goal was equal rights and protections for women in education, under the law and in the workforce. I had found my career focus.

“RBG” featured much archival footage. There were early photos and home movies of Ginsburg’s life. There was also coverage of early feminist marches and protests. One still shot featured women wearing tee shirts emblazened with the logo for the United Nations International Women’s Year – a dove enveloping the biological symbol for a woman. That was back in 1975, a seminal year for me. In addition to doing women’s labor advocacy work in the US, my duties increasingly extended to learning about and working with women from other countries.

At the time, I didn’t realize that my work on international women’s issues would lead directly to a life-changing opportunity. After several years, I became restless with my job, feeling I would hit a glass ceiling at that union before long. So, like a lot of my college classmates, I began applying to law school. Halfway through the process though, I knew studying law was not for me. I couldn’t even bring myself to finish the applications.

Instead, a serendipituous encounter with a college friend opened another avenue. When I whined of my half-hearted desire to attend law school, he said: “What do you really want to do?” Immediately, I responded: “I want to live in Italy.” He shared that Oberlin, our alma mater, offered alumni fellowships to such endeavors if they were backed with an academic focus. I submitted a proposal to study the role of women in Italian labor unions within the context of UN International Women’s Year initiatives. My proposal was accepted. Shortly afterward I began night classes learning Italian at Georgetown University.

Though the fellowship from Oberlin was modest, it was enough to prompt me to request a leave of absence, plan for my year abroad and start to bring my few belongings to my folks’ place in Pennsylvania. Just before I was to leave for my year in Rome, another opportunity opened up. My employer decided to participate in a training program for women active in transport unions throughout Southeast Asia. My last assignment, along with my director and another friend of ours, a feminist psychologist, was to co-teach at this program held in Penang, Malaysia.

There were women from ten Southeast Asian countries present. We, as American feminists, were sent to spread the good news of women’s liberation and to encourage union activism among our female ranks. We gave workshops focused on assertiveness and other issues. The women soaked up what we had to offer and we had very rich cultural exchanges. But there was additional icing on the cake for me.

Rather than return to the States after the Malaysian program to begin my leave of absence, I chose to keep going west, traveling for more than two months before reaching Rome. Through my contacts in the US labor movement, I had set up meetings with women’s activists and trade unionists in Indonesia, Thailand, Bangladesh, Nepal, India and finally, Egypt. What an experience for a twenty-five year old, working-class girl from New Castle, PA. I sometimes pinched myself to believe it was real. I had intended to visit more countries, getting visas before leaving the States for travel in Iran and Afghanistan. It was only after being on the road in Asia that people began to warn me, as a single woman, against those stops. I was naive about the level of anti-American sentiment and the rising role of the conservative clerics and the Taliban.

It wasn’t always easy: I became ill with parasites that plagued me for a year afterward, and I grew lonely at times. But I kept moving and met many fascinating people along the way. Asia became for me the multicultural place it really is, expanding my previously-limited notion of it as China, Japan and Vietnam. The trip was mind-blowing! Though I had traveled and lived previously in Latin America and Europe, my Asia experience truly opened the world’s diversity to me.

Just as the future Supreme Court justice was slowly building a foundation for groundbreaking legal precedents in the US, the women I met on this trip were forging new paths for women – who were denied equal rights in nearly all realms of their societies. Many were eager to learn about American feminism and I learned a lot from them. And I would to learn and contribute to the ongoing force of women’s rights as I entered the next phase of my life’s journey – my year in Rome.

To be continued –

“White Chrysanthemum” is a historical novel, published “in 2018, by American author Mary Lynn Bracht. This bold endeavor shines a light on the nearly-forgotten history of the so-called “comfort women” exploited sexually by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. It took determination to stay with Bracht’s telling of the brutality of the era. Bracht subjects are the young girls and women abducted from their homes or tricked into sexual slavery. She does not shy from the horrors they suffered at their captives’ hands. The details sometimes come with a strong emotional punch.

“White Chrysanthemum” is a historical novel, published “in 2018, by American author Mary Lynn Bracht. This bold endeavor shines a light on the nearly-forgotten history of the so-called “comfort women” exploited sexually by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II. It took determination to stay with Bracht’s telling of the brutality of the era. Bracht subjects are the young girls and women abducted from their homes or tricked into sexual slavery. She does not shy from the horrors they suffered at their captives’ hands. The details sometimes come with a strong emotional punch.